Millions of undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. face deportation under President Donald Trump's immigration enforcement orders. To accomplish this task, Trump is reviving federal enforcement policies that authorize and deputizes state and local law officials to catch, detain and remove non-citizens back to their country of origin.

An estimated 70,000 undocumented immigrants live in Arkansas, according to the Pew Research Center which monitors immigration trends. Many working families, raising American-born children, fret their lives will be ripped apart by Trump’s mass deportation order. A coalition of Arkansas human rights activists are stepping forward hoping to intervene.

Soon after he took office, President Trump announced a series of Executive Orders directing the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency to purge the nation of immigrants residing illegally in the United States. To rally more troops, he's redeploying Secure Communities, launched in 2008, by President George W. Bush in response to millions of immigrants from Mexico and Central America surging across the U.S. border settling in places like California, Texas, and Arkansas. Secure Communities gives local law enforcement the authority to check federal databases to determine the immigration status of detainees in custody. If found to be in the country illegally, ICE agents initiated deportation. Secure Communities resulted in the removal of more than 400,000 individuals — one third of them convicted criminals.

President Barack Obama ended Secure Communities in 2014 after widespread reports of racial profiling and immigrant families being torn apart. Obama ordered immigration law enforcement to focus only on criminal aliens. During Obama’s final year in office, 240,255 removals occurred nationwide, with 92 percent of individuals convicted of a criminal offense.

Trump plans to build out Secure Communities as well as section 287(g), enacted in 1996, under the federal Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act.

The 287(g) program funds collaboration between federal and local authorities, in effect deputizing local law enforcement to act as immigration enforcers?. Between 2006 and 2013, more than 175,ooo immigrants were removed under the program. In Arkansas, four local police and sheriff departments in Rogers, Fayetteville, Bentonville and Springdale signed joint 287(g) memoranda of agreement, allowing specially trained officers to investigate, arrest and detain citizens suspected to be without citizenship papers.

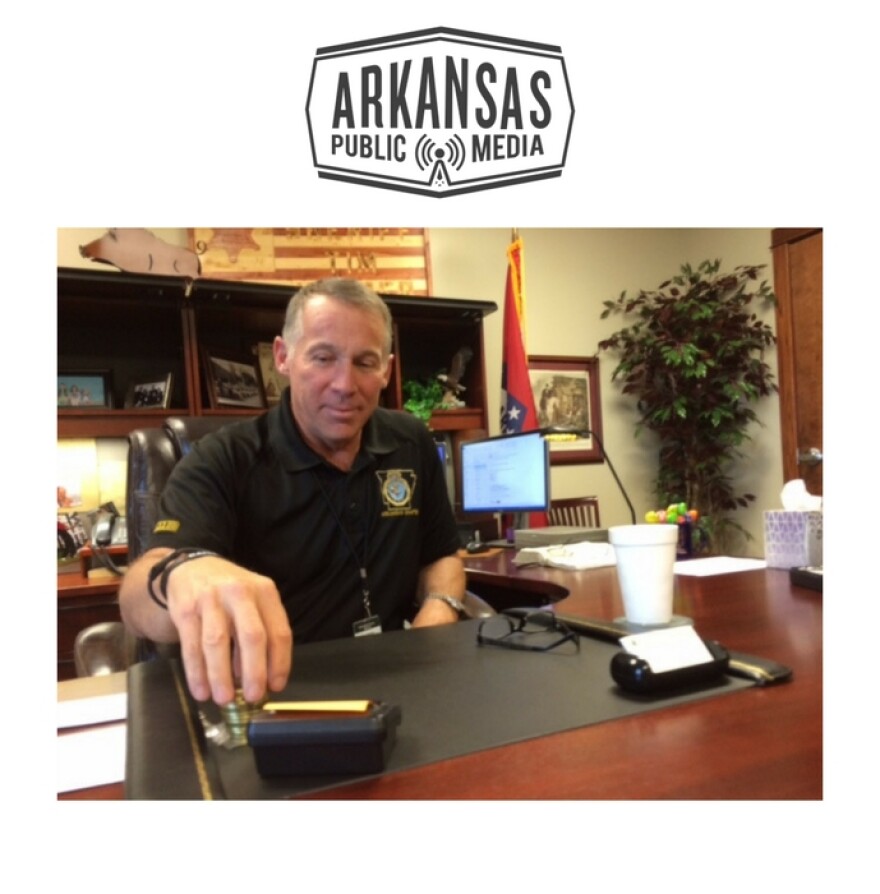

Today, only Benton and Washington county sheriff departments maintain 287(g) agents, says Washington County Sheriff Tim Helder.

“Anybody that’s arrested, they fill out their booking information, which lists country of birth,” Helder says. “If it’s anything outside of the United States of America, it basically sends a flag to be checked.”

Sheriff Helder was not able to furnish 287(g) detainment records. He referred us to the regional Immigration Customs and Enforcement Field Office in Louisiana, responsible for Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee. Thomas Byrd, field office public affairs officer, offered to furnish Arkansas data for this report, but days later, rescinded, saying a formal Freedom of Information Act request would be required.

Instead, we sought data from Juan Jose Bustamante, an assistant sociology professor at the University of Arkansas who researches U.S. immigration enforcement outcomes nationally and in Arkansas. He found that between 2007 and 2012, a total of 1,511 of 287(g) removals occurred in Arkansas, with 875 unauthorized individuals living in Benton County and 636 in Washington County--indicating just how robust the program was in Northwest Arkansas.

Springdale immigration attorney Stephen Coger, through Freedom of Information Act requests, also provided data for this report, gathered specifically on Washington County Sheriff’s Office 287(g) activity. In 2016, 110 detainer requests were submitted. This year it's been just ten.

Coger says he's worried that Trump's executive actions ramping up immigration enforcement are forcing Arkansas's established immigrant community back into the shadows.

“Prior to 287(g), entire families would shop in the local marketplace,” Coger says. “After, families would send only one member, to protect everyone from being arrested.”

Of nearly 2,000 287(g) agreements nationwide, many have lapsed. Seventeen states, including Arkansas, however, continued to renew such agreements across 42 county jurisdictions. In December, 2012, Rogers Police and Springdale Police Departments’ agreements expired. Washington County Sheriff Tim Helder has one assigned 287(g) deputy and insists he will only detain criminally charged individuals.

“When I say this,” Helder says, “not everyone is going to be a drug dealer or rapist or a bank robber. There will be people that come through our doors that may have a warrant for a misdemeanor offense — I don’t know.”

Misdemeanor offenses, which may include not having a driver's license or wearing a seatbelt. Helder also says his office no longer takes ICE reimbursement for detainment costs because he cannot comply with the agency’s strict accommodation rules.

Just how many Arkansas law enforcement agencies will sign back onto Secure Communities and 287(g) remains to be seen. The Arkansas State Police says it does not presently participate. Springdale Police Chief Mike Peters, whose jurisdiction is the most culturally diverse in the state, says he doesn’t either.

To raise awareness about threats to immigrant families in Arkansas, the Arkansas Justice Collective will stage an event Saturday on the Fayetteville town square, a planned press conference, rally & gospel show to encourage Washington County Sheriff's Office to protect rather than deport law-abiding immigrant families.

No undocumented families settled in Arkansas were willing to come forward to discuss their concerns. Stephen Coger says he’s not surprised. Citing several cases of detainee neglect, verging on abuse in northwest Arkansas, he says unauthorized immigrants, including law-abiding individuals, don't want to risk being identified.

“I can speak as someone who works with immigrants every day and have seen the fear multiply exponentially. I hear it in their voicemails they leave me. I see it in their children’s eyes, as we discuss their parent’s immigration situation.”

Coger says he supports federal immigration enforcement, but only if it complies with due process and targets real criminals. Federal immigration enforcement authorities are given broad powers to search out, detain and deport undocumented individuals without warrants.

“What I want is for ICE to have to do a little more work and get a warrant," Coger says.

Soon after taking office, President Trump ordered expansion of a domestic “deportation force,” hiring 10,000 new U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and expedited removals to quickly deport undocumented immigrants caught at the U.S. border — turning back any number of individuals seeking political asylum. Federal immigration sweeps are also on the rise, taking place across the country, including the surrounding states of Oklahoma, Texas Missouri, and Tennessee — but not yet in Arkansas.

To raise awareness about immigrant families in the state, the Arkansas Justice Collective is staging an event Saturday on the Fayetteville town square. "Don’t Deport Dad" is a planned press conference, rally & gospel show, encouraging the Washington County Sheriff’s Office and other Arkansas jurisdictions to protect rather than deport law-abiding immigrant families.

This story is produced by Arkansas Public Media, a statewide journalism collaboration among public media organizations. Arkansas Public Media reporting is funded in part through a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with the support of partner stations KUAR, KUAF, KASU and KTXK and from members of the public. You can learn more and support Arkansas Public Media’s reporting at arkansaspublicmedia.org. Arkansas Public Media is Natural State news with context.